The Southland by Matt Tyrnauer

An excerpt from our new book "Design Commune"

11.20.2020

This month, we’re incredibly proud to announce the release of our second book, Design Commune. We asked our longtime friend, lifelong Angeleno and prolific Hollywood director Matt Tyrnauer, to write an introduction that would seek to unify the myriad projects within the book. What Matt turned over to us was a deeply contemplative and meticulously documented account of what it means to be a group of people designing together in (and for) a city of migrants. This was the through line for each of our projects. Matt helped us understand how being situated in Los Angeles gives us a complicated relationship to architectural history; he posits that this is thanks to the “city's liberal attitude toward artistic endeavor”. And it’s true. We have a crazy sort of belief that anything is possible if you dream it and draft it, no matter what has come before. It’s this psychosis that has fueled us through the projects we’re so excited to finally share.

We’ve chosen to publish Matt’s full introduction because it so perfectly captures the vernacular of Angeleno design and helps explain who and what we are as Commune both in our city and abroad. We’ve gone through the text and added a superscript to the locations and people Matt mentions, hoping to provide a helpful visual guide to his historical narrative.

—

When it comes to making observations and depictions of Los Angeles, outsiders almost always have a more interesting perspective and a greater ability to interpret and synthesize the mercurial culture of the city. Of course, the rare native occasionally hits the bullseye. Bret Easton Ellis, for example, who singlehandedly defined certain aspects of the 1980s for the permanent record; likewise, Walter Mosley and James Ellroy for the 1930s and 1940s; and Robert Towne for the late 1930s and the 1970s, and P.T. Anderson for the 1990s. And yet, consider just some of the visitors and transplants who have been the main cultural interpreters, and, ultimately, the most heroic definers of the place: David Hockney (West Yorkshire, UK); James M. Cain (Annapolis, Maryland); Ed Ruscha (Omaha, Nebraska); Evelyn Waugh (London, UK); F. Scott Fitzgerald (St. Paul, Minnesota); Jessica Mitford (Gloucestershire, UK); Hal Ashby (Ogden, Utah); Charles and Henry Greene (Brighton, Ohio); Joan Didion (Sacramento, California).

Los Angeles, as a city of immigrants, self-selectors, and self-reinventors, is a place where, as the historian Garry Wills once observed, the “natives arrived the day before yesterday rather than yesterday.” Thus, the Southland, as the greater city is disconcertingly called by local newscasters, has been, since mid-century, the ultimate American arrival city, willing and able to absorb and nurture a diverse array of cultures, many of whom have been pleased to discover a zone of creative free expression, far less hemmed in than eastern cities—particularly New York—by societal strictures and the rules of the game. LA is a giant, commodious, at times puzzling but liberating blank slate. This essential characteristic has allowed many creative minds to work at full tilt and dispense with a lot of the dues-paying that other more hidebound cities require.

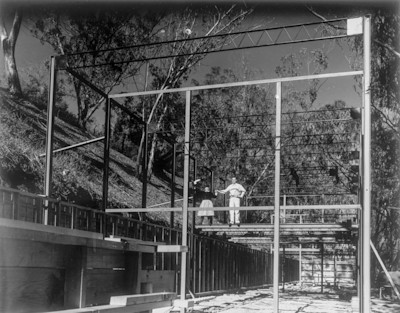

No other field has benefited more from the city’s liberal attitude toward artistic endeavor than architecture and design. In a town where there was no historic tradition to which to adhere (the once-prevalent “Spanish” theme of LA architecture is just that, a theme, riffing off of the Pueblo Revival style of the Spanish colonists, itself a riff on colonial architecture south of the border) the tabula rasa proved a blessing. By the 1920s, Rudolph Schindler and Richard Neutra, both from Vienna and both one-time associates of Frank Lloyd Wright (from Richland Center, Wisconsin), were working in Los Angeles in competition with Wright, and redefining Modernism in America with their houses, apartments, and mixed-use structures all over the region. They, in turn, had been influenced by the radical early California modernist Irving Gill1 (originally from Tully, New York). The 1922 Schindler House2, at 833 Kings Road in West Hollywood, was a watershed moment for Modernism, considered to be one of the most important houses of its time, both for its avant-garde precast “lift slab” concrete construction, and for its function as a communal live-work compound. Schindler and his wife, Pauline, in fact, shared the house with Neutra and his wife, Dione, for five years in the 1920s, setting a provocative and resonant precedent for a kind of Bohemianism in what was then not-quite-yet the movie capital of the world, but a provincial, emerging city set among orange groves, barley, and oil fields between the Santa Monica Mountains and the Pacific coast. Once again, outsiders were pushing things forward in lotusland. Who would have guessed that Viennese Modernism would adapt well on the Pacific Rim?

In the late 1970s, as a child, I saw the Schindler House for the first time. My parents brought me to a party there being thrown by a group of hippies, who had adopted it for their urban commune, at a time when the general population of LA didn’t give a damn about Schindler or Neutra’s Modernism, and many aging Modern houses were considered to be eyesores and labeled “tear-downs.” As squalid as the house was, stripped of most of its original fixtures (Schindler died in 1953), I remember being beguiled. It all seemed very edgy, different, and even dangerous (though that may have had something to do with the exposed, frayed wiring hanging out everywhere, and the cracked linoleum laid over the original cement floors). It was my first true awareness of LA Modernism and it suddenly reoriented me and inspired me to seek out the neglected and hidden Modern architectural history of my hometown.

In a book cataloguing the best of LA architecture by Charles Moore, then dean of the architecture department at UCLA, I found the rest of Schindler and Neutra’s buildings. My friends and I diligently went to see them all, knocking on the doors of the houses, asking for tours. Frequently, the people who had commissioned the houses were still living in them. They were delighted to have a gang of middle-school students interested in their homes. The most important house closest to where I lived was the Eames House3 (built, in 1949, as part of the Case Study House Program sponsored by Arts & Architecture Magazine), which sits on a bluff overlooking the Pacific, near Santa Monica. My friends and I, with trepidation, used to gun our cars up the steep driveway, and then get out and walk about the Eames property. We’d linger in the famous meadow in front of the iconic structure, and peer into the windows of the living room, where all of Charles and Ray Eames’s craft objects were on display, just where Ray, who was still living in the house at the time, had placed them. Ray never appeared. Charles had died more than a decade before.

How powerful it was to see that Eames living room intact! The taxonomic array of the Eames’ craft and textile and furniture collections in the living room contrasting wholly with the clean, minimalist lines of the glass-and-steel house. It was a study in bold contradiction and enormous aesthetic confidence, and it had, at one time, been the nerve center and creative incubator of the vastly influential Eames operation, which was, much like the Schindler House of its day, a design commune.

The Eameses (he, originally from St. Louis, and she, a native of Sacramento), met at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. They set out in 1941 on a “honeymoon road trip,” which led the couple to relocate permanently to Los Angeles. Their first residence, after putting up in a hotel for a time, was Neutra’s Strathmore Apartments in Westwood4. Charles and Ray began molding their famous plywood into chairs in the second bedroom of the apartment. They soon found more adequate work spaces on Abbott Kinney Boulevard in Venice, which became the storied Eames Office5, the most significant multi-disciplinary design studio in the United States, if not the world—and a next-generation version of the collective/collaborative notions of Schindler and Neutra a generation before. The Eames Office produced an astonishing array of architecture, industrial design products, textiles, and even a string of award-winning films, all infused with an optimistic and accessible design approach that did much to define mid-century modern American life. The Eames Office’s holistic approach to design across disciplines was its hallmark, and, thanks in large part to the dynamic partnership of Charles and Ray, as well as the charismatic master salesmanship of Charles, the Eames Office became the ne plus ultra of industrial design in LA (and far beyond), with hooks into every commercial sphere of consequence: aerospace, military, government, architecture, and consumer product design, both for the carriage trade as well as the mass market. The success—as well as the publicity—was enormous and lasting. Moreover, they made it look so easy. Of course, none of it was easy. The Eameses—and the design team that supported them—were, in fact, outliers, whose acumen and celebrity inoculated them against the potentially deadly forces of suspicion that ruled life in mid-century America. It wasn’t all groovy optimism: It was also the McCarthy era, when anything collective or communal—or obviously foreign as Schindler and Neutra were—was considered suspicious. The special Southern California subsect of McCarthyite politics, the John Birch Society, was particularly alert to any artistic type who could be pegged or smeared as a pinko or a degenerate, or both. If the more radical (and less successful) Schindler had lived past 1953, he may have been ostracized totally. Thus, as a measure of self-preservation, the Eames Office and Richard Neutra were loaded up with patriotic government contracts, which not only paid the bills, but mitigated any suspicions of radical un-American activities in their respective studios. They survived and thrived, and coaxed the ethos and the cityscape of the Southland.

Neutra died in 1970, and Charles Eames died in 1978, and, sadly, the era of integral California Modern they did much to create, virtually died along with them. The High Modern architecture heritage of the city was almost entirely neglected in the last decades of the 20th century, treated like a cute fad, misunderstood, abandoned, and frequently slated for obliteration. As real estate values drive almost every aspect of life in Southern California, the Modernism of the city was doomed by realtors and developers, who brought on an era of faux Baroque McMansions and strip malls in the style of gigantic Taco Bells or a seven-car garage designed by Michael Graves. The aesthetics of Orange County—seat of the John Birch Society—were encroaching on, and nearly overtaking, the more human-scaled, individualistic domestic architecture of the County of Angels. When would, or could, the madness stop?

There were, in the years before the turn of the millennium, some signs of hope, among them the revival of interest in the unloved Modern houses, which became known as mid-century Modern houses. Architecture groupies began to buy and restore them. Preservation movements took hold, and a new generation of designers began to refer to the LA Modern aesthetic in their work, and, more vitally, these designers could find work from tastemakers and thought leaders who were obsessively restoring the iconic, surviving examples of domestic Modern architecture. The structures gained totemic status. They were no longer mere houses; they were sculptures to collect—and to live in.

As a correspondent for Vanity Fair magazine at that time, part of my job was to record and canonize these acts of architectural mercy. One day, Helmut Newton alerted me that a friend of his, the German publisher,Benedikt Taschen, was restoring John Lautner’s 1960 Chemosphere house6, which looms over Mulholland Drive like a wood-and-glass flying saucer.

Helmut and I went over to see Taschen, and he did a spontaneous photo shoot in the Chemosphere. As Helmut had neglected to bring a tripod, he asked his photo assistant to lock him in a bear hug to make the shot stable. Helmut clicked away, bellowing the whole time, “Hold me, baby! Hold me, baby!”

I wrote the story of the house and Taschen’s fascination with Los Angeles for the magazine. Taschen, a major art collector, who runs a salon out of the Chemosphere living room, soon befriended his next-door neighbor, David Hockney7. Now Hockney is a regular on the built-in banquettes in a conversation nook of the Chemosphere living room. Each time I witness the ex-patriot publisher from Cologne, Germany, and the son of Yorkshire —collector and maestro—together in conversation next to Lautner’s mod hearth at the center of the lovingly restored spaceship house, I feel as if I am observing a baton being passed between the outsider/emigres who continue to define high culture of the city. Through the CinemaScope picture windows of Lautner’s masterpiece, the light grid of the city that beguiles us all spreads out toward the silhouetted mountain backdrop.

Around the same time I wrote this story about Taschen and the Chemosphere, I was asked to write another article about a new design firm that was taking off in town. It seemed to me that Commune, founded in 2004, was at once a throwback and a harbinger. As the name announces, the firm takes a collectivist approach to its work—shades of the Eameses—and its two lead designers, Roman Alonso and Steven Johanknecht, have a deep knowledge and abiding appreciation of the design heritage of the city they work in. At the time, in 2007, they had just created a store on Rodeo Drive that was a throwback to the luxurious brutalism of the ’60s and ’70s era of travertine temples for Gucci and Neiman Marcus. It was a welcome break from the faux Via Condotti wave that overtook Beverly Hills shopping streets in the 1990s—yet another symptom of Orange County’s imagineered sensibilities overtaking LA.

Sixteen years on from the Vanity Fair piece, it’s clear that Commune was, in fact, the leading edge of what has become an arts and design revolution in Los Angeles, fueled by creative people across many disciplines, flocking to the city, where rents for studio spaces are still comparatively reasonable—certainly in relation to New York and London. Commune itself has also stoked the flames of this LA arts Renaissance by commissioning an astonishing roster of artists, craftspeople, and artisans (many based in the city) to collaborate with them on their projects. The long list includes Alma Allen8 (sculpture and furniture); Lisa Eisner9 (bibelot and objet); Stan Bitters 10 (ceramic sculpture); Adam Silverman (ceramics); Tanya Aguiñiga 11(fiber art); the Haas Brothers 12(mixed media and murals); Adam Pogue13 (textiles); Samiro Yunoki 14(textiles and illustration); Ido Yoshimoto15 (wood sculpture and furniture); Louis Eisner 16(murals).

In the Vanity Fair article, Johanknecht told me, “We are facilitators not dictators,” pointing to a more idealistic form of communism—if you will—which harkens back to the shared studio/home of Schindler, and the creative impulses that made the “city of future” idealism of LA so attractive to the pre-war generation of designers who migrated here from Europe, the eastern architecture schools, or, like the Eameses, the multi-disciplinary, crafts-oriented Cranbrook Art Academy outside of Detroit.

It goes without saying that Alonso and Johanknecht are both from somewhere else. Alonso was born in Caracas, Venezuela, and later moved to Miami, before starting his career in Manhattan in fashion PR. Johanknecht is from Syracuse, New York, and, before he relocated to Manhattan, commuted to New York City on $20 People’s Express weekend flights to attend Studio 54. The pair first worked together at Barneys New York as members of an in-house creative team, responsible for everything from the store interiors to the display windows to advertising, and the famous no-expense-spared launch parties, a hallmark of the era when the Pressman family still presided over what turned out to be the last glorious gasp of the department store era.

Alonso noted in Vanity Fair that when clients come to their first meetings with Commune, “We really make them talk to us almost like therapy sessions, and bring totemic objects.” The totemic objects in the Eames living room come to mind. These were moved around and rearranged obsessively by Ray Eames, and are as integral to the iconic house as the boxy steel girder construction and the colored panels of the facade. The cool minimalism of the High Modern, cut with the expressive taste of the inhabitants. Alonso and Johanknecht’s instincts are, likewise, to make things that are bespoke and personal, and as far from standardized and overly manufactured as possible. “We help clients find their genetic make-up and develop their own language and style,” said Johanknecht. According to Alonso, “Steven and I have never been afraid to step outside what’s usually expected of a more conventional design studio. Size or type of project or style is not the most important thing. What we love most is an interesting challenge and diversity for the team. Many studios have a signature look, and although some people would say we do, we don’t see it that way. We work hard to bring out what should be our client’s aesthetic. We help them figure out what their world should look like. If we are successful, it looks right for them.” They are, in effect, helping you channel your inner Ray Eames.

The diversity and range of Commune’s various projects bears this out: The Ace Hotels, including the Palm Springs and Los Angeles branches, are definitive examples of adaptive reuse—the former touching off a new wave of hotels in the desert that have sensitively reinterpreted Palm Springs Modernism, and the latter reviving an entire swath of LA’s early-20th-century downtown theater district. Stores for Heath, the California pottery concern, create a casual sense of artisanal luxe, and likewise, a meticulous Spanish Colonial home restoration in the Los Feliz section of LA. At the other end of the California vernacular design spectrum is Commune’s reinterpretation of a craftsman house in Berkeley.

Branching out from their Los Angeles home base, and disseminating the Commune ethos, the group is behind the Goop flagship in Manhattan; the Caldera House ski club in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and an Ace Hotel in Kyoto. “The design of the Ace Kyoto,” says Alonso, “is rooted in the idea of East meets West through craft. Both Japan and California have a long tradition and respect for craft, and the inspiration came from the cultural exchange brought about by Japanese Americans like Isamu Noguchi, Ruth Asawa, and George Nakashima, and from the collaboration between western designers, like Charlotte Perriand, and Japanese craftsmen. For the project, we actually recruited a long list of Japanese artists and artisans, as well as Californians. The only American artists and craftsmen working on the project are from California, so it’s kind of Kyoto meets West Coast.” Moreover, he adds, “The architect on the project is Kengo Kuma, who has never collaborated with an American interior designer, so in that sense it’s also Japan meets California.”

The Commune office, with their collaborators and in-house designers, who work in teams, has the air of a laid-back Wiener Werkstätte. One notes that the computer screens around the office are not only filled with renderings of interiors, but also of textiles, rugs, tiles, super graphics, furniture. They even have a line of chocolate in collaboration with Valerie Gordon, the confectionary queen of the fast-gentrifying LA neighborhood Echo Park. Confectionary queen, bespoke design studio, and Echo Park were not categories that went together just a handful of years ago—yet another example of how Commune has been a catalyst for making LA a cultural loadstar in the present time.

“Four years ago, we got rid of all hierarchy in the studio—teams, departments, etc.,” says Johanknecht. “Now we are truly an open studio where our designers work as one large team and are involved in some way on all projects. To us, designing a poster, a napkin, a chair, a trailer, a house, or a hotel is all the same. We see it first and foremost as problem solving.” Alonso adds, “Our staff”—which currently numbers twenty—“reflects Steven’s and my background and interests. Varied and unexpected. Fine artists, an architect with a masters from Harvard, a doctor in sociology, former industrial designers, etc. They all have a love of the type of work we do and are team players. Those are the only true requirements for entry.”

Johanknecht concludes, “We’ve never been stuck on being anything in particular or been precious about what we do. We’ve always been honest about who and what we are. We simply see ourselves as a full-service design studio that is always open for collaboration and for business.”

I recently asked Alonso and Johanknecht to survey their Commune team to see how many of them are, like the majority of the key designers of the Southland aesthetic, from somewhere else. “Only three are from LA,” Alonso says.

Migrants, as ever, shape the land.