Shaker

Technology has offered us a lot, but the basics — the simplest forms — remain the most appealing. In the US, those simple forms we admire have been largely shaped by a small group of religious folks in New England, known as the shakers.

11.28.2019

“A Shaker chair, spare and elegant, will give instant and familiar visual pleasure to the eye schooled in modernist design. But like certain strains of modernist art – geometric abstraction, say – it may also be read as an ideal of order and balance, which has particular urgency in an uncentered late 20th- century world.” An excerpt from the New York Times on August 2, 1996. This is a beautiful sentiment. When all feels uncertain, unknown or "uncentered", we turn with urgency to the traditions that ground us, to the "balance" from which we came. We set off in search of the basics, and come up to the surface with the common denominators that link us all. Design is at the mercy of this right now. And on this week of tradition making, in this time of unrest, we're exploring a foundational tenet of American design.

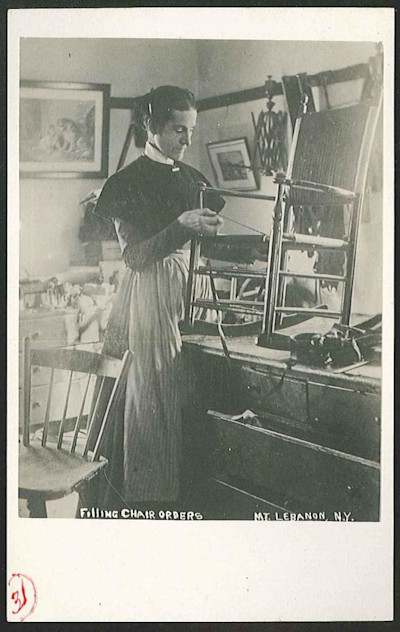

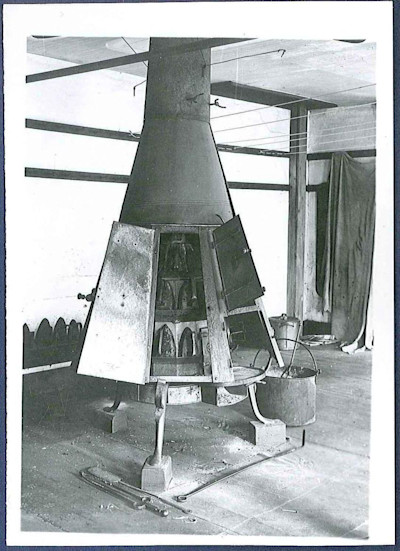

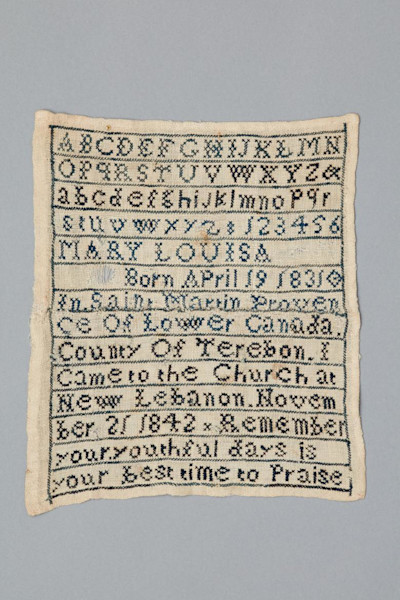

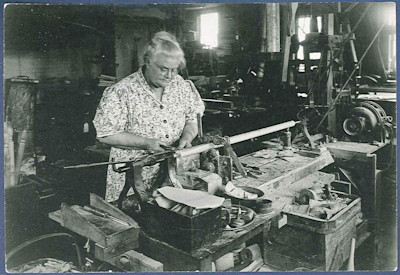

Technology has offered us a multitude of hands with which to manipulate and experiment beyond our wildest dreams, but the basics -- the simplest forms -- remain the most appealing. Since 1776, those forms have been largely shaped by a small group of religious folks in New England known as the Shakers. Living under rigid lifestyle mandates which demanded humble work, the Shakers rejected unnecessary adornment in all of their surroundings. They believed in the principle notion of an ideal form and of honesty in materiality, which needn't be manipulated. At the core of Shaker design was a reliance upon these things that we can all share -- a simple piece of local wood, the necessity for practicality, the acceptance of natural imperfection. This is what we admire so much about the design. It is at its core democratic, it is accessible, and it offers beautiful solutions to the everyday lives of the people using the spaces.

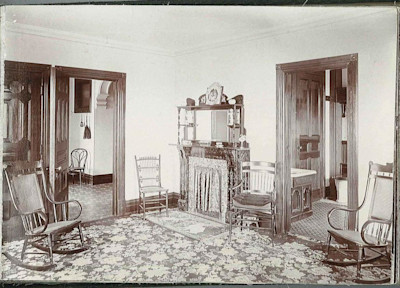

Each image here is an example of Shaker design between the years of 1776 and 1937, at which point their community was dispersed. Each piece of furniture, bottle of medicine, or tool exemplifies the Shaker belief that form should not undermine function, but should enable it.

The following images are from the archives of The Shaker Museum in Mount Lebanon, NY and from the Metropolitan Museum Archive.