John Outterbridge

A timely exploration of one of LA’s artistic historians.

02.25.2021

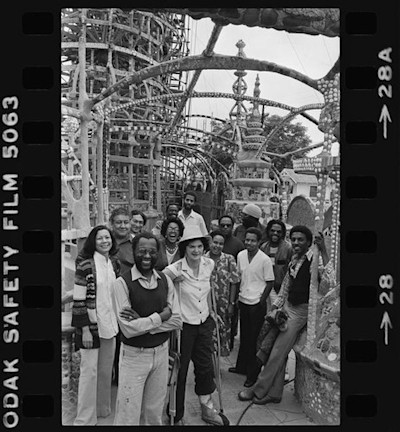

As we continue to dissect the immense creative output of our home city, we learn of artists who reveal to us the intricacies of this wild place, the tendrils of 'LA' as seen through their own lived experience in this vast metropolis. One such artist, John Outterbridge, was a community activist throughout his artistic career in LA from the 60s through to his passing at the end of last year. This position as activist first and artist second marked the course of his legacy entirely as he explored his identity through his practice.

Born in Greeneville, North Carolina, Outterbridge was raised by a father who made a living by recycling discarded equipment, machine parts, construction materials and the like. His childhood was one of discovery by way of exposure to the byproducts of our society and what comes of objects after we deem that they are no longer of value. Outterbridge brought with him this familiarity of found objects and the penchant for repurposing materials when he relocated to LA in 1963. It was only fitting that he would eventually go on to assume a role as the director of the Watts Towers Arts Center, as the Watts Towers were painstakingly built out of materials found on construction sites — rebar, concrete, wire mesh — and decorated with over three decades of found objects.

From a wide angle, Outterbridge’s personal oeuvre is vast in scope, but his fascination with assemblage underscores it all. His paintings began to be combined with found objects shortly after he moved to LA and had the contents of this city at his disposal. It was a tumultuous time for this city; a period of deep reckoning was underway. While the Watts Riots consumed the streets from 1961 through the better part of the decade, Outterbridge began to collect debris from the riots and incorporate them into his artwork. These found object assemblages were highly charged, they carried with them the pain that generations suffered under racist laws, policies, and societal norms. What resulted was inherently political, steeped in history, and grounded in place. This sort of work became emblematic of Outterbridge’s career. He continued to rely on his art not just to make things to put into museums but to communicate the reality of everyday life for him and his community. It’s critical that we take the time to truly witness these works for the teachers of history that they are.

For more information on his work and his role as director of the Watts Tower Arts Center, we highly recommend watching this episode of the PBS series, ARTBOUND.