From the Library: Hollywood Life

Imagine being a photographer in 1969 in Hollywood. These are the photos you would take, and the story you would tell.

12.24.2020

When we’re in need of inspiration, our library is the first place we turn to; it exists in the physical and symbolic center of our office. In an effort to immortalize the countless resources on its shelves, we feature a pertinent title from our library in each issue of the Post.

—

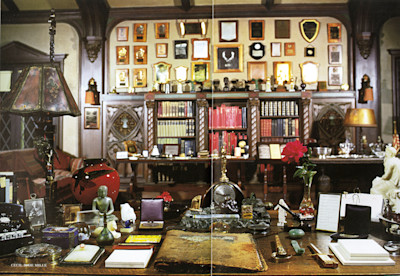

This month, we’re reading “Hollywood Life: The Glamorous Homes of Vintage Hollywood”. If you’ve been reading along this year, our city has inspired us immensely. We’ve written about its beautiful ugliness, the artists who call it home, and how lucky we feel to be in its sunshine. But this month, we’re indulging in the Hollywood of our city. The part of LA that the world is fascinated by and we don’t often allow ourselves to take part in.

“Hollywood Life” is a series of incredible photographs taken inside the homes of stars in the late 60’s by Life photographer Eliot Elisofon. They’re intimate — voyeuristic almost — and offer a rare unplanned picture of the lives, homes and people featured. We’ve chosen to reprint the foreword written by Gavin Lambert, as we are particularly interested in his interpretation of Hollywood and the transplants that inhabit it, pondering how it has come to be such a vast conglomerate of unapologetic and individualistic style. Lambert writes that the hopefuls arriving in Los Angeles brought with them a “nostalgia for what they left behind” which “created an architecture of exile, gingerbread gables, 'art glass', front porches and those high slanted roofs designed back East for the snow to slide off.” We love this idea that the so-called architecture of exile very much found a permanent home here in LA. It is a beautiful tribute to the city we’ve explored so deeply this year.

—

In the early 1870’s, before the ‘movie people’ came, immigrants from New England and the Midwest began uprooting themselves to Southern California. Those who settled in Los Angeles found a small town with unpaved streets and vast tracts of land for sale at bargain prices. But although the immigrants came in search of a better climate and new lives, nostalgia for what they left behind created an architecture of exile, gingerbread gables, “art glass”, front porches and those high slanted roofs designed back East for the snow to slide off.

By 1912, when the first wave of movie people arrived, Los Angeles had become a small but sprawling city where Iowa Gothic and New England Colonial existed alongside a few surviving haciendas, reminders that California had once belonged to Mexico. A recent development was the stucco “bungalow court,” rental units that accommodated newcomers who couldn’t afford to buy, or were unsure if they wanted to stay. They were especially popular with the movie people, who waited to build their own houses until 1920, when oil strikes and a booming movie industry launched the bonanza years.

Yet only a few chose to live in Hollywood itself, an area bounded north and south by the Hollywood hills and Beverly Boulevard, east and west by Hoover Street and Doheny Drive: Alla Nazimova – in a house that eventually became the Garden of Allah, Rudolph Valentino, Clara Bow, Jean Harlow, Norma Shearer and Joel McCrea, who was born there. Ten years later, every major star, director and producer had abandoned Hollywood for Beverly Hills, Bel Air, Santa Monica or the San Fernando Valley; and to escape the doormen and waiters whom the gossip columnist Hedda Hopper employed as spies, a few stars moved to Malibu.

Although they still returned for the movie premieres at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, and to work at Paramount, RKO or Columbia Studios, “Hollywood” became a generic word for anybody and anything connected with the movies. “ALL ROADS LEAD TO HOLLYWOOD,” according to a huge neon sign that flashed on and off every night above the Newberry store on the Boulevard, but “Hollywood” life was lived anywhere from a cowboy star’s ranch in the Valley to a new-Colonial manor house with guests arriving for a formal dinner while coyotes howled in the Santa Monica Mountains.

And the movie colony’s public life originally centered on downtown Los Angeles. The Brown Derby on Wilshire Boulevard became its restaurant of choice, and the Cocoanut Grove, adjoining the Ambassador Hotel across the street, its most popular night club. Bootleg liquor flowed at all star private parties, and on Saturday nights the dance floor, fringed with palm trees acquired from Valentino’s The Sheik after its desert set was struck, became the arena for a Charleston contest, where Jean Peters (later Carole Lombard) and Lucile Fay Le Sueur (later Joan Crawford) invariably competed for first prize.

From 1930 until 1936, the Grove hosted the annual Academy Awards ceremony; and by that time, three states high in the hills of Beverly – Pickfair, Harold Lloyd’s Greenacres and John Barrymore’s Bella Vista – and the Hearst-Marion Davies Ocean House on Santa Monica beach, had established the grand tradition of movie star living. Essentially showplaces for the rich and famous, and stocked with the fine imported antique furniture, their models were either Old World or Old Mexico, British stately home, palazzo, “Riviera,” Spanish Colonial, hacienda, and sometimes a mixture of the last two. Fountains and “classical” statuary decorated the gardens – and in the case of Ocean House, a Venetian bridge spanned the swimming pool.

Although an invitation to dinner at Pickfair was considered the highest social honor, at least one guest found it a “deadly” experience. For Gloria Swanson, whose own showplace was famous for its perfumed elevator, the grandeur couldn’t disguise an atmosphere of provincial respectability. It seemed to inhibit regular guest like Chaplin, John Gilbert, Norma Shearer and Irving Thalberg, Hearst and even Marion Davies. Limiting them to only one cocktail before dinner (which began promptly at seven), and one glass of wine during it, was no doubt partly responsible. And after an eight-thirty movie screening, the couple generally acknowledged as Hollywood royalty added a final middle-class touch: a cup of Ovaltine “for the road.”

The second generation of movie people built mansions that were still spacious and expensive, but on a more moderate, human scale. The two most important belonged to George Cukor and Edie and William Goetz. Cukor’s Italianate-Mediterranean villa above Sunset Strip was shielded by a high wall, with a narrow gate that opened automatically after you announced yourself on the telephone in an adjoining niche. The interiors, designed by William Haines in his dramatically effective mix-and-match style (chandeliers, Chinese Chippendale mirrors, Regency commodes, Victorian armchairs) contained a very personal art collection, paintings by Picasso, Matisse, Juan Gris and Braque, a Tchelitchew drawing and a portrait by Sargent of Ethel Barrymore – who often stayed in the guest suite. During her last visit, when she was suffering from emphysema and a friend mentioned that Bette Davis and Gary Merrill were about to open in The World of Carl Sanburg at the Huntington Hartford Theatre, Barrymore famously gasped, “Thanks for the warning.”

Another frequent guest, Somerset Maugham, wrote a screenplay based on his novel The Razor’s Edge in the suite. But instead of Cukor, the director Maugham hoped for, Fox assigned Edmund Goulding to the movie, and discarded Maugham’s screenplay.

Beyond the pool, the grounds sloped uphill to a guesthouse, where Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy lived for several years. Like Barrymore and Maugham, they were part of one of Cukor’s inner circles, an eclectic group that also included Garbo, Artur Rubinstein, Ava Gardner, Aldous and Laura Huxley. Another circle, larger, wider and equally eclectic, comprised show business friends who didn’t live in Los Angeles. For Noel Coward, Vivien Leigh and Cole Porter, Cukor threw parties that he called “the full Hollywood thing with fountains and bands.” The guest lists ranged from Judy Garland to David O. Selznick, Merle Oberon to Garson Kanin, and Moss Hart to Garbo, who surprised everyone by prompting Porter when he forgot a line while singing one of his own songs.

The high wall on Cordell Drive also assured privacy for the players in Cukor’s personal. These included a group of handsome, charming and gay young actors from New York, whom he’d cast in small roles when he was directing plays on Broadway, and who hoped for screen careers when he moved to Hollywood. But although their strongest talent was not for acting, Cukor loyally cast them in minor parts. Other players besides male beauties in the third circle were gifted camp performers like Rex O’Malley, who played Gaston in the Cukor-Garbo Camille, and Grady Sutton, a “sissy” in the glorious Franklin Pangborn tradition, notably in several movies with WC Fields. Like the beauties (beginning to fade by the late 1930’s), they became regulars at Cukor’s Sunday afternoon pool parties, where call boys in briefs paraded love for sale.

Like the other great houses, Cukor’s was a world in itself; but unique in the way he lived and worked simultaneously as an outsider (gay) and insider (whose most successful mainstream films were often his best, and marked by an artist’s personal style). By contrast, the world of the Goetz house was for insiders only. In the same year, 1930, Louis B. Mayer’s two daughters, Irene and Edie, had both married young and ambitious studio executives. But while David O. Selznick became a genuinely creative producer, William Goetz remained a company man at Fox, then at Universal, and finally at his own company, which enjoyed only one brief moment of glory with Sayonara.

Unsurprisingly, the brothers-in-law never became close friends; and the sisters became distant enemies. “The worst person I’ve known,” Irene once remarked about Edie, who worked hard to establish herself as Hollywood’s leading hostess, and had succeeded by the time David produced Gone With the Wind. Many of the guests in the Goetz’s Holmby Hills mansion were Cukor familiars, but Cukor himself, who had directed several Selznick production, was never invited to these formal occasions – and nor, on account of Irene, was David. The Goetzs assembled a formidable collection of French impressionist paintings, and a guest list drawn from the cream of the Hollywood establishment crop (Cary Grant, Gary and Rocky Cooper, James and Gloria Stewart, Darryl Zanuck, Irene Dunne, Loretta Young). After dinner at a long, candelabra-lit table glistening with silver, overlooked by a Bonnard on one wall and a Degas on another, a Renoir on one of the living room walls disappeared as a movie screen was lowered in front of it.

Soon after David Selznick married Irene, he bought a new-Colonial house on Summit Drive in the hills of Beverly. While he produced movies, Irene produced Sunday parties; marathons that began with afternoon tennis and usually ended around two in the morning. After David left her and married Jennifer Jones in 1949, Irene sold the property, and a few years later David bought a Spanish colonial house on nearby Tower Grove Road. Originally built by John Gilbert, the owner at the time was Miriam Hopkins. Hopkins, a southerner who was bitterly disappointed not to be cast as Scarlett O’Hara, had transformed Gibert’s dark baronial interiors to airy Moderne with here and there a plantation home antique. The Selznicks ordered more extensive remodeling, and one notable addition was the canopied terrace, where another long dinner table accommodated a varied and lively selection of guests. On a typical evening you might encounter a few of David’s former colleagues, King Vidor, Lewis Milestone, Joseph Cotton and his wife Patricia Medina; a Jungian psychoanalyst; visiting Moroccan and/or Spanish royalty; and Sylvia, Lady Ashley, daughter of a London policeman, former chorus girl, breeziest of femmes fatales, who had married two English lords, Douglas Fairbanks Sr. and Clark Gable, and as a final coup, would become Princess Djordjadze when she took a Balkan royal for her fifth husband.

In 1965 Selznick had a fatal heart attack in his Tower Grove study, where he’d summoned his business manager to discuss how to pay off some of his most pressing debts. Five years later Jennifer sold the house and married millionaire art collector Norton Simon. Meanwhile there were no more parties, and after Bill Goetz died in 1969, the long dinner table in Holmby Hills also stood empty. For another twenty years Edie lived alone with the same extensive staff of servants, and her memories of behind-closed-doors Hollywood gossip (including how her father lowered the boom on Norma Shearer’s affair with Mickey Rooney), confided to a few visitors but never to the press.

Goetz’s death marked the end of what Cukor used to call La Belle Epoque. Even though Cukor lived on until 1983, there were no more grand parties on Cordell Drive either, because only two starry friends from that époque survived him: reclusive Garbo in her New York apartment, and Hepburn, a working actress until she was 87, but also living on the east coast and out west only for an occasional Hollywood film. Cukor himself, a working director until he was 81, lived energetically in the present as well as the past, hosting small dinners for Truffaut, for Paul Morrissey and Andy Warhol, and surviving members of the original gay circle.

Long before John Barrymore died (predictably early in 1942), the famous aviary at Bella Vista had become as deep in filth as its owner lay deep in booze and debts. After Hearst died in 1951, Marion Davies sold Ocean House, which became a hotel; and when she died in 1961, the hotel had failed and was due to be razed to make way for a beach parking lot. By that time, the remaining grand traditional estates were, like their owners, in decline. Indifferent to leaks in the roof and rips in the upholstery of Pickfair, Mary Pickford had also taken to the bottle, in the privacy of her bedroom as opposed to Barrymore’s public flamboyance; Harold Lloyd, ignoring Greenacres' cracked walls and flaked gold-leaf ceilings, concentrated on photographing pubescent girls in light summer dresses, posed against vistas of unweeded gardens and fountains that produced only sad trickles.

From the 1960’s to the millennium, only James Coburn and his wife created a genuine movie star showplace, their engagingly over-the-top Arabian Nights fantasy on a 1920’s scale. A few others chose to live like the major stars they never became. While George Hamilton settled on a mini-estate in a vine-covered mansion, whose bedroom flaunted a chandelier, an armoire and an imperial four-poster that looked like custom made imitations, Tina Louise wrapped herself in an enormous fur coat and struck a faux Dietrich pose on the stairs of her home. As for Bobby Darin, his taste would have made even Liberace blush.

But a majority of the third generation favored a more modest and personal style of living and entertaining. In her comfortable and unpretentious Brentwood house, Natalie Wood confined memorabilia of a starry career to the den, and gave parties that were neither A or B list. Guests might be famous (Ruth Gordon and Garson Kanin, Mia Farrow, Roddy McDowall, Michael Caine) or not so famous, but they were always friends.

Among her famous friends was Rock Hudson, whose hacienda style house in Beverly Hills was known as The Castle – but not on account of grandeur. In 1928 Lloyd Wright, who created the acoustic shell for the Hollywood Bowl, had designed a modernist fortress for Ramon Novarro. Built on a sparsely developed Hollywood hilltop, it could never be overlooked. Although times had changed in many ways since then, a gay actor who was also a romantic icon still needed the equivalent of a drawbridge to protect his privacy; and even though Hudson’s Castle sat on a hilltop it hid behind a wall as high as Cukor’s.

Beyond the wall, in the courtyard entrance, statues of nude boys confronted the visitor; inside the house, dogs and lovers abounded, bridge games were another favorite sport, and dinner parties, gay or mixed, (with Elizabeth Taylor or Claire Trevor of Martha Raye among the mixers), were always for friends.

The best Hollywood homes, creative and playful, celebrated not only pleasure and fulfillment but also personal freedom. They reflected a wide range of choices, to be royally or modestly grand, grandly or genuinely modest, to have a place where you hung your hat in private or publicized your image. But detractors of “Hollywood excess” should take a look at the Palacio Nacional da Pena in Sintra, built for a king of Portugal, or the Palacio de los Capitanes Generales in Havana, built for the Governor of Cuba (both palaces now impeccably preserved as UNESCO world heritage sites), or at photographs of Leopoldskron, the castle near Salzburg, after a theatre director Max Reinhardt acquired and furnished it. “Excess,” in fact, has a long, gorgeous history that reaches back to the houses of medieval Damascus, and to Topkapi Palace. And the great Hollywood houses, whether “Italian Renaissance” like Greenacres, “neo-Bizantine” like Gypsy Rose Lee’s opulent interiors, or “hacienda” like Edith Head’s classic Casa Ladera, reflected the same desire for elegance, prestige and splendor as their avatars.

Most of them survive in photographs, but too many have been erased by the bulldozer. The Barrymore and Selznick-Jennifer Jones homes went under it years ago, and at the time of writing, the former Ira Gershwin residence has a date with it. Developers have subdivided Greenacres, and are angling for the Cecil B. de Mille estate. The houses of George Cukor and Edith Head have endured the kind of face-lifts that erase personality as well as wrinkles. Among public building, the original Brown Derby and its Hollywood satellite have gone, and “renovation” has subjected the exterior and the lobby of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre to a severe identity crisis.

Los Angeles has vastly expanded in the last thirty years, of course, and in general the buildings that have replaced so many Hollywood landmarks confirm Arnold Toynbee’s belief that geographical expansion usually coincides with a decline in quality. But time is an even more powerful enemy than the developer, the bulldozer and (as they say in real state circles) the “fixer-upper.”

Great houses are inevitably stripped of personality when their owners move on, to another home or another world. Soon after George Cukor died, his secretary asked me to pick up a book that he’d wanted me to have. And as I walked past the gardens and the pool, still as intact as the rooms inside the house, the place seemed waiting to be haunted, not only by George but by Garbo and Artur Rubinstein, Noel Coward and Vivien Leigh, Somerset Maugham and the call boys, Katharine Hepburn and the Huxleys, and all the other players in one Hollywood life.

–Gavin Lambert “Hollywood Life” (Greybull Press, 2004)