From the Archive: Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Hill House

The contrasting beauty of a Glaswegian architect.

03.22.2025

Before diving into the work of one of our most revered inspirations, it helps to pause on the movement from which he emerged: symbolism. Understanding European symbolism offers an explanation for the otherworldliness found in even the smallest details of Mackintosh’s designs, and particularly of those found in his famed Hill House. Symbolism was a movement in direct contrast with realism. Symbolist writers, for instance, relied on metaphors and floral language to convey stories filled with mysticism and the telling of dreams. Mackintosh’s work, being decorative, imaginative and spirited, gave physical form to a similar sentiment.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh was born in Glasgow in 1868 just after the end of the Industrial Revolution. This was a monumental time of growth for the city, as it sat as the heart of the shipbuilding and engineering industry worldwide. In step with this massive physical growth, Glasgow became a city interested in consuming new forms of global art and design and began the twentieth century deeply inspired by its newfound foreign influence (ie Japanese botanical motifs became ubiquitous). The modest pragmatism of an industrial town remained inherent to Glaswegian design, even as philosophies began to shift and accessibility to art was in demand by the masses. This cultural mix set the scene for the growth of the Art Nouveau, which was a time for celebration of the decorative arts and the dissolve of any distinction between “fine” art and applied art. It was this setting that saw Mackintosh through his education at the Glasgow School of Art and eventual career as an architect, interior designer, writer, and painter.

Commissioned by Walter Blackie in 1902, the Hill House was conceived by Mackintosh to function perfectly for the family that would eventually inhabit its grounds. Mackintosh spent an extensive amount of time with the family before breaking ground, as he felt the most successful design began with function and followed with beauty. He was given several directives by Blackie, leading to the infamous grayish exterior (namely no red-tiled roof, no bricks, no wooden beams… all of which were exceedingly popular at the time). What resulted is a sober looking building seeming to sink in repose into the gray of the Scottish countryside, only to reveal an intricate other world within.

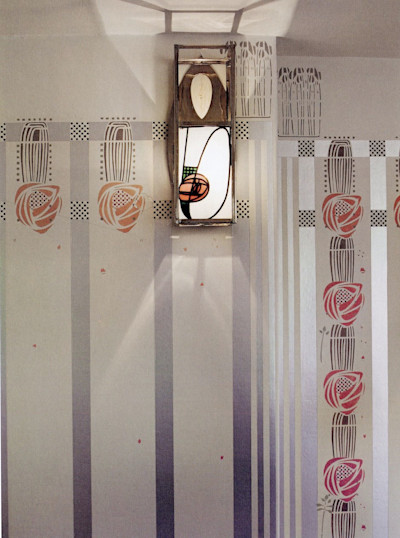

The interiors of the Hill House could really be dissected forever. They offer a striking balance between art nouveau flourishes and a more minimal approach to modern functional design or in other words it is a balancing act between industrial and natural influence. Contrast exists everywhere. It’s in the color scheme, as dark wooden trims encase pale, patterned blocks of wallpaper and textiles (all customized for the house and designed by Mackintosh). It’s in the design of the furniture emerging both delicate and strong, with details both artful and practical. There are motifs repeated throughout the home such as checkerboards and grids which are thoughtfully interrupted by branching florals (again, offering a contrast). Perhaps what is most ingenious about the Hill House composition is the way in which it is the contrasts that draw attention to each detail. Without the simplicity of the furniture forms, for example, the textiles may not stand out as well. Mackintosh led with this restraint as he designed every single detail on this home.

Images here are from GA Residential Masterpieces: Charles Rennie Mackintosh which was edited and photographed by Yukio Futugawa.